- Home

- Barry Wolverton

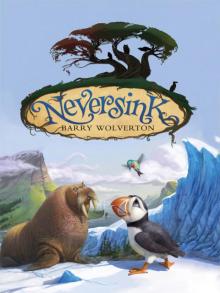

Neversink

Neversink Read online

Neversink

A Puffin Saga

By Barry Wolverton

With drawings by Sam Nielson

Dedication

For my mother.

Neversink, indeed.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Map of Neversink, Tytonia, and various points of interest

Birds of the Northerly World

Epigraph

Prologue: A Most Forbidding Place (Unless You’re an Auk)

Part One: A Smidgen of Fish

1. Perchance to Soar

2. The Great Auk and the Littlest Owl

3. The Plot in the Parliament

4. The Worst Party Ever (Unless You’re a Walrus)

5. Murther Most Fowl

Part Two: Over Sea, Under Ground

6. The Fish Tax

7. A Smidgen Too Far

8. The Worst Party Since Chapter 4

9. Captured!

10. Missing

11. Down the Badger Hole

12. The King’s Final Solution

13. Death on the Moors, or The Bittern’s Lament

14. This Is Good-bye

Part Three: Ocean’s End

15. Voyage of the Shunned

16. Lucy’s Last Stand

17. In the Temple of Knowledge

18. The Oddest Sea

19. The Return

20. Rozbell’s Clutches

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map of Neversink, Tytonia, and various points of interest

BIRDS OF THE NORTHERLY WORLD

Excerpted from THE WALRUS GUIDE TO LESSER CREATURES, Sixteenth Edition

AUKS

Plump, duck-like seafarers with rapid, buzzing flight. Nest in dense, noisy, often malodorous colonies; “fly” underwater and prefer tea with their fish.

Puffin: Smallish, squidgy, improbable looking. Relatively quiet and well-mannered, except when provoked. Not to be confused with a penguin, or a parrot, or a cross between a penguin and a parrot.

Razorbill: Largest of the Neversink auks. Only one sensibly named, after its distinctive wedge-shaped bill. Creaking “urrr” or harsh “arrr” call. Renowned for skill in carving wood and ivory.

Murre: Largish, with a long narrow bill. Purrs, croaks, and growls, depending on mood; can dive more than 300 feet; nests high on cliffs, presumably out of snootiness.

Guillemot: Medium-sized. Unnecessarily florid name. Noisy, disagreeable, with bright orange-red tongue often displayed impolitely. Grating, high-pitched “peeee” call.

OWLS

Mostly nocturnal birds of prey, distinguished by forward-facing eyes and legendary wisdom. May or may not have visible ear tufts, called horns. May or may not wear hats.

Snowy owl: Day-hunting white owl preferring open hunting grounds. Large, heavily feathered feet to protect from cold; yellow eyes. Cold habitat reputedly matched by cool disposition.

Pygmy owl: Smallest but most ill-tempered of Tytonian owls. Ambush hunter with undulating flight like the woodpecker’s. Prone to violent outbursts, physical and verbal tics, and delusions of grandeur.

Scops owl: Tall, slender horned owl of phlegmatic humor. Resembles an overgrown moth. No idea what “scops” means.

Great gray owl: Large, dark barred owl with relatively small yellow eyes. Known for driving off predators as large as black bears when defending nest. Like many large owls, often overly self-satisfied.

Epigraph

Unsnack your snood, madanna, for the stars

Are shining on all brows of Neversink.

Already the green bird of summer has flown

Away.

—WALLACE STEVENS,

“Late Hymn From the Myrrh-Mountain”

PROLOGUE

A MOST FORBIDDING PLACE (UNLESS YOU’RE AN AUK)

If you were to follow the imaginary line known as the Arctic Circle all the way around the world, you would eventually land on a small island called Neversink, whose shores are lapped by the icy waters of the Great Northern Sea.

Not that you’d want to. Rugged and wintry, Neversink was forged by fire from an undersea volcano. The ground is like teeth and the wind lashes like a whip. The interior is a bleak landscape of glacial ice caps, ancient black basalt, and frozen soil called tundra. Wild grasslands and soggy bogs cover the warmer southern regions, but there are few trees because of the lack of rain. In summer the sun scarcely sets; in winter it scarcely rises. And volcanoes disguised as snow-capped mountains erupt without warning, carving the scarred surface anew with flowing lava.

But the jagged southern coastline, where sheer cliffs and moss-covered rocks rise above the bays and fjords, was once the perfect home for a group of seabirds known as auks. Short, stubby, black-and-white birds, all with funny-sounding names to match their funny-looking appearance: Razorbill. Murre. Guillemot. Puffin. Neversink was home to the largest population of these strange birds in that part of the world—the colony of Auk’s Landing.

These are birds who happily spend much of their time at sea, eat fish, fly underwater, and are not to be confused with penguins. On Neversink auks could nest safely in the nooks and crannies of the island’s ice-gouged rocks, far away from the perching birds of nearby Tytonia, protected from predators by a girdle of ocean, safe from most threats other than old age and an unpredictable sea goddess named Sedna.

So had it been since the Age of Settlement. And so would it have remained, many believe, if Rozbell had never tasted Lucy Puffin’s fish smidgens.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. For now, you should know that the world of this story is one that existed long ago and is no more. The continents had formed and separated but were covered with forests. The dinosaurs were long gone. Humans did not yet roam the earth, much less rule it. In short, it was a bird’s paradise.

And as you may have guessed from the cover of the book, one bird in particular, once upon a time, behaved heroically enough (or foolishly enough, depending on who you ask) for someone to write about him.

Of course, you might not be reading this story at all if walruses couldn’t talk. I know what you’re thinking. All animals can talk. Some can even sing, dance, and play golf. But it was walruses, after all, who came up with the notion of converting talking into writing, so that future generations of animals could enjoy all the many wonderful things walruses have to say.

One walrus in particular was, I believe, the author of A Short History of Neversink, which is the source of the story I am about to tell you. How can I be so sure? I think once you read on, you will understand completely. Or not. By the end you may not remember you read this.

And why not just read A Short History of Neversink? Let me assure the reader that, while walruses are great scholars of the first order, they operate on a scale alien to mere humans. To a walrus, for example, to weigh less than four thousand pounds makes you “slim.” And a meal of fewer than three thousand clams is a “light snack.”

Along those lines, there is nothing short about A Short History of Neversink. (A Short History of Neversink is actually a multivolume set that is part of the multi-multivolume set A Long History of the Whole World, which would take the average human more than one hundred fifty years to read.) Despite the important research and fantastic stories contained within, the author, like all walrus authors, is given to numerous and lengthy digressions about whatever may tickle his whiskers—chiefly, the importance of food, the acquisition of food, the preparation of food, and the eating of food. There are also many passages devoted to the excellence of the walrus mind and the importance of the walrus opinion. Trust me when I tell you that most of this is of little interest to the

nonwalrus.

So, consider the story in your hand a translation of sorts. I have even changed the names of some things and places to their contemporary names to help you, dear reader, better understand this strange world.

PERCHANCE TO SOAR

At the outer reaches of Auk’s Landing, there was a high, narrow ledge that jutted out over the sea and curved to a point like a sharp bill. Over the years, this isolated spot had become a kind of sanctuary for Lockley Puffin, to escape the chaos and clamor of his fellow auks.

If you know anything about puffins, you know they don’t quite fit in with their seafaring kin. You see, auks as a group look very much alike, with their black-and-white plumage and webbed feet. The puffins’ large, colorful bills and bright orange legs made them objects of suspicion in a colony where Blend In and Don’t Make Waves were the guiding principles of life.

And even for a puffin, Lockley had a habit of sticking out in all the wrong ways. In fact, Lockley had earned a reputation as a bit of a troublemaker.

He didn’t mean to be (a troublemaker, that is). But puffins are known for being relatively quiet among the auk families—their appearance is loud enough—and so it was very noticeable when one wasn’t (quiet, I mean).

Like the time the Parliament of Owls decided Neversink could no longer import cranberries from Tytonia without paying a hefty “transportation fee.” Parliament, the lawmaking body of owls that governed the kingdom of Tytonia, knew how much the auks enjoyed making cranberry scones. Everyone agreed it was a brazen attempt to punish Neversink. (And for no good reason, at that.)

But only Lockley wanted to raise the issue with the Great Auk, the colony’s law-speaker. Surely Parliament’s actions violated the Peace of Yore—the treaty that had made Neversink an independent colony of Tytonia. What did it mean to be independent if, at the end of the day, you were still controlled by owls?

To the colony’s dismay, the Great Auk agreed it was worthy of a vote to decide whether to protest the decree. The colony voted almost unanimously to do without cranberries. Don’t Make Waves.

It was exactly this sort of unpleasantness that caused Lockley to retreat to his private place. He stood there now, looking toward the horizon. It was that time of day on Neversink when sunrise mirrored sunset. The sun was just above the water, bruising the sky. The water was a deep, dark, humpback gray, except for a strip of light cutting a path from sun to shore, inviting Lockley to walk across it. Lockley liked to imagine that such a celestial path guided his ancestors to Neversink when they were forced to leave Tytonia.

Lockley gathered up the fish he’d caught that morning and clasped them in his bill. His wife, Lucy, would be expecting him back by now. But he had something else to attend to first. Something not even Lucy knew about. He stepped to the very edge of the precipice and shook out his wings. His breath came quickly, but it was neither owls nor auks that were agitating him. He was trying to learn how to soar. He was embarrassed by the buzzy, frantic flight of puffins and other auks, who had to beat their wings rapidly to keep their squash-shaped bodies above the water. Even then, they often veered wildly, tossed by the Northern Sea’s wind gusts. He didn’t think it was very bird-like.

It was bad enough to be awkward on land. Lots of seabirds were. But the albatross, the petrel, and the sea eagle, once airborne, all circled high toward the sun, coasting on thermal updrafts, gliding on the wing. How wonderful it would be to float above the sea and enjoy the solitude of the heavens. Lockley wanted to be like them, a sky roamer.

And so, his heart beating even more fiercely than his wings, Lockley put his feet together and launched himself from the cliff, toward the sky. Up and up he went, until he felt the thermals beneath him…lifting him…carrying him. He stopped flapping, spread his wings wide, and began to coast with effortless power. It was a thrilling sensation. Until, as always, doubt weighed him down. Doubt that said, Puffins aren’t meant to soar.

And slowly, slowly, he began to fall.

North of Auk’s Landing, Neversink’s towering sea cliffs gave way to sloping lava fields, tide pools surrounded by tiny islands of black rock, and flat stretches of sand that the seals and seabirds called the beach.

Now, if the word beach brings to mind tropical postcards or warm summer vacations, think again. Picture instead a shoreline that looks like the colossal warty foot of a giant dipping his toes in the ocean. And standing on this scarred and rocky ground was an especially large walrus, looking with some concern at an object in the sky while a frenetic hummingbird darted back and forth from one side of his head to the other.

“What do you think it is, Egbert?” (into his left ear). “A comet?” (into his right ear). “An asteroid?”

“Hardly.”

The flying object came nearer…a dark projectile, tumbling, wobbling, hurtling recklessly through the air.

“Is it a bird, Egbert?” asked the hummingbird.

“Doesn’t look like any bird I’ve seen,” the walrus patiently replied.

“Is it a plane?”

“There’s no such thing as a plane!”

“Is it a flying sack of onions?”

“Ruby, there is no such thing as a flying sack of—”

And in that moment of distraction, it crashed. Right into Egbert, to be precise. There was a sound like a cannonball hitting mashed potatoes as the flying object collided with a mound of walrus flesh, bounced to the ground, and rolled to a lumpy stop.

“Lockley! Good heavens!” said Egbert. “Are you okay?”

Lockley sat up, dazed. He shook his head from side to side until the giant walrus and the tiny hummingbird came into focus.

“I think you bruised one of my ribs!” said Egbert, rubbing his side.

“There are bones under there?” said Ruby.

Lockley wobbled to his feet. “Terribly sorry, Egbert. I didn’t see you there.”

“You’re kidding, right?” said Ruby. But Lockley ignored her as he cleaned up his mess. The fish he’d been carrying had scattered all over the rocks, and as he gathered them up, he plopped them into an enclosed tide pool, where there was already a school of small, silvery fish known as sand eels—a favorite of puffins.

Egbert peered into the pool. “Lockley, are you eating fish or collecting them?”

“Both!” said Lockley. “What I mean is, they’re not just for Lucy and me.”

“Are they for me?” said Egbert, his whiskers twitching with excitement.

“Are they for me?” said Ruby.

“Hummingbirds don’t eat fish,” Egbert shot back.

“Oh, yeah.”

“They don’t customarily live near Ocean’s End, either,” Egbert reminded her.

“They aren’t for either of you,” said Lockley. Egbert shrank with disappointment, before Lockley added, “Not directly, anyway. Egbert—Lucy has agreed to make her world-famous fish smidgens for your surprise birthday party!”

“Really?” said Egbert.

“Surprise!”

“What’s so surprising?” Ruby asked. “Egbert planned the whole thing himself!”

Egbert struggled to maintain his composure. “Dear, dear Lockley. You and Lucy are such dear, dear friends.”

“Come to think of it,” said Ruby, “how did you get the whole colony to agree to come to your party?”

Egbert righted himself and said, “I simply explained to them that I planned to reveal something that will dramatically change all their lives for the better.”

“Oh, right,” said Ruby. “You lied to them.”

“I did not lie to them!” said Egbert, and he was prepared to defend himself with great gusto, when suddenly he turned to Lockley and gave him a critical look—the kind of look that usually preceded one of his lectures. “Lockley, why were you flying like that?”

“Like what?” said Lockley, fidgeting.

“Like you were launched out of a catapult,” said Ruby.

“There’s no such thing as a catapult,” said Lockley.

�

��Lockley…you were trying to soar again,” said Egbert, pointing an accusing fin at him.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“You could have broken your neck hitting these rocks from that high up!” Egbert scolded.

“Good thing there was a million pounds of blubber here to break your fall,” said Ruby.

“I am quite normal-sized for a walrus!” Egbert bellowed.

Lockley sighed as his friends fell to bickering again. Unlike puffins, Egbert and Ruby seemed to enjoy sticking out, and one was never happy if the other was commanding too much attention. Egbert, after all, was the only walrus on Neversink. Most of his kin lived in large clans near the North Pole. He claimed to be on a mission to spread the walrus gifts of learning to the rest of the world, Neversink being his first stop. The auks had long ago given up hope that he would ever leave.

Ruby was even more of a stranger. Her family was from what humans would call the New World (it was new to them, anyway). South America, to be exact. While migrating north one summer, she was blown off course and forced to make a rest stop on Neversink. Lockley and Egbert had never seen such a curious thing, and their attention was like sugar water to the proud little hummingbird. Now Ruby summered there every year, sustained by the wildflowers that grew on the grasslands during this milder season.

The Vanishing Island

The Vanishing Island The Sea of the Dead

The Sea of the Dead Neversink

Neversink The Dragon's Gate

The Dragon's Gate